Subscribe to CX E-News

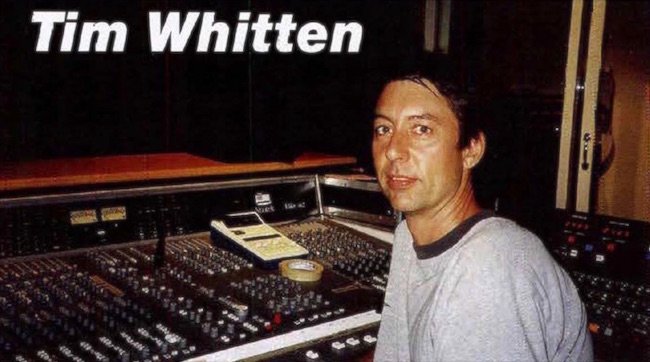

The Producer – Tim Whitten

From the archive: In February 1998 Connections Magazine began a series of profiles on Australian record producers, written by Madeleine Murray.

After an hour of conversation, Tim Whitten struck me as a particularly sane person. If I didn’t know he was a music producer, he could have passed for a doctor or a young, better looking Paul Keating. During the years he toured with bands like Beastie Boys, Devo, Alice Cooper, and Cult, he must have been a perfect chord in a chaotic world.

Rumour has it that he doesn’t do drugs, and there is absolutely nothing neurotic about him, compared to some wild characters. Leonard Cohen once told me about his Phil Spector recording experience, which involved guns and savage dogs.

Unfortunately for a racy article, it’s hard to find anyone with a bad word to say about Whitten. Words like judgement, decency, tact and discretion come up.

He seems to inspire respect and affection in people. Even adoration and midwife metaphors in some, like Lindy Morrison, drummer for the Go Betweens. Whitten was the band’s monitor engineer for two years in Europe. “One of his most redeeming qualities is not just his technical prowess, but his manner,” Morrison said.

“He never ever breaks under pressure, and he never scapegoats the drummer in the band, which other producers have done, particularly in the 80s, during the advent of the drum machine. Tim’s always interested in real sound.”

Whitten admits that he is not liked by everyone, all the time. Once he mixed a record as a favour, at mate’s rates. The friend liked the mix, brought it home, and the band decided they didn’t like it. And they wanted Whitten to pay for a remix.

He feels a bit hurt and baffled when a band, who has a good record with him, moves onto another producer, and puts out a less successful effort. A long term relationship produces a certain shorthand.

“I think it’s really important to nurture a recording relationship,” he said. “Whenever you pick up a new producer or engineer, you have to get to know them, to work out how you each respond.

“That’s a whole learning experience in those first days, the crucial time that you are putting down the beds of the songs that you build on. Those days are very important, that’s where the structure, the intent and the feel come out.”

Jason de Wilde was in a band called Pelican Jed, when Whitten produced their EP. “He was kind of quiet in the studio, l guess he was concentrating,” de Wilde said.

“He was very particular about sounds. He’s certainly one of the nicest guys I’ve met in the music industry. He doesn’t really push his weight around, but lets the band have their ideas, and then expands them.”

Whitten was engineer on Glovebox’s ‘Umbrella.’ Singer/guitarist Tony Dupe found him easy going, focused, very polished, and a perfectionist, in a good way. He’s smooth with fader movements and good at changing levels subtly. His attention to detail is remarkable.”

First, listen to the songs

When Whitten first works with a band, he likes to listen to the music at home, imagine how it could sound, and make notes. That could be shorter some sections, cutting, extending. He gets a feel for the overall look of the song, and talks to the band about their ideas.

“Obviously, it’s a very delicate matter,” he said. “I don’t dictate, but ask them for their suggestions. What overdubs, strings, percussions, do thay want to add in the studio?

“I try to find a common thread between their vision of the song, and mine. The band’s initial ideas remain intact, but the music becomes a little more listenable, or challenging, or unusual.”

Whitten is tactful “It’ll become apparent if there’s any conflict. I approach the band carefully about making changes if I think they might be really sensitive about it.

“Rather than tell t1em there’s a problem, I’ll try and show them: it could work better another way. It’s always important for the musicians to feel that they’re in control. I’m there really as a catalyst, but I do make changes.”

Af1er they have worked out arrangements they go into the studio. “I might have a reservation about something, but I won’t mention. it. Because often things change,” he said.

Next step, the subconscious

In the studio, as engineer, Whitten positions the mics, instruments, and arranges isolation. “That depends on how the band feel. I try hard get at least bass, drums, and one guitar down together, hoping to keep all three. Mainly because music works in en emotional sense.

“I work out which is the most comfortable way for the band to play the songs, in order to get a good feel. That means focusing on the bed of the song, which could be the basic melody,and the basic rhythm. If those things gel together then I can overdub with counter rhythms, counter melodies, or whatever.”

Whitten gets the band to go through a song, and records it, “hopefully without them knowing I’m pressing the record button.

“The trick to getting a good performance is for the musician not to be overly concentrating on recording. There needs to be some kine of detachment for the subconscious to work.”

He only goes through a song a few times, because the band lose their freshness. “You have to create some kind to tension, some kind of feel, and it’s very hard to do that, if you’ve been recording the song ten times.”

Whitten uses compression in the recording stage on particular instruments, and in the mixing stage. “It depends on the instrument. Generally I’m always using some compression, because it helps bring out detail and textures of sounds.

“You can have a very strong level on tape, and a very low noise floor, which is good for vocals. I mainly use compression to gain some textural change to an instrument Something which initially sounds a little weak and uneven can be made to sound quite present and confident with compression.”

After all the overdubs and vocals are done, Whitten feels that the picture is blocked in. Then the details are worked on. “It’s very easy to fall into the trap of thinking you can fix it in the mix.” (When he told me that, I wondered if he knew the other two great lies of the music industry, but I didn’t ask.)

“You can change a song completely in the mix. I try to find the essence of the song. It might be one little guitar line that works with the vocals.”

Style

He likes to create large subtle soundscapes, and sonic blends. “It’s hard for me to do something direct, where everything is at the same level. I hope my mixes have clarity and sense of space.”

Eno’s work with U2, Martin’s with the Beatles, and Steve Albini are favourites. “With U2, Eno challenges everything that’s going on, he will find the gem of the song among 20 guitar tracks.

“Albini focuses so intensely on the pure energy and rawness. His approach is the opposite of mine. He has the ablility to make bands feel very uncomfortable, which creates a tension that comes out on tape.

“You can hear the band is pisssed off, and hating every moment of it. With some types of music, that’s an advantage”

From Connections Magazine, February 1998. Read full edition here:

https://www.cxnetwork.com.au/cx-magazine/connections-february-1998

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.