News

13 Jun 2018

Automixing – your extra hand

Subscribe to CX E-News

REGULARS

Automixing – your extra hand

Simon Byrne.

I can see you’re frowning already. I’m the mix engineer! No computer algorithm can possibly do a better job than me! You are right… and wrong.

In mixing high profile conferences and unscripted events, the challenge is that you don’t always know who is going to talk next, which means you are forced to keep lots of mikes at least partially open, so you struggle for gain before feedback and get room noise. Enter the automixer.

Automixing mimics the action of a human operator: increasing gain for “talking” mics and at the same time, reducing gain for all others, but doing it much more quickly than a human could and keeping the amount of total gain constant, so a clean live mix can be created. It is an aid to a tighter, cleaner sound, with consistent ambience which is less prone to feedback.

On high-end events it does not replace the human operator, but assists them. You still do your mixing art, with the help of the automixer keeping things clean in the background.

There have been various attempts at automixing, the first being loosely based around noise gates, but experience has shown that in most live situations it isn’t possible to find a gate threshold that will work without obvious chopping. Once the level passed the gate’s threshold, the channel would open up so the voice is heard.

Because it has to sense sound before it opens up the channel, it was never great. If the threshold was set too high, the start of words would be chopped so “Good Morning ladies and gentlemen” would become “ ood orning adies nd entlemen”. If the threshold is set too low the microphone stays open so

it does not work.

Even worse, if the threshold is set correctly but the speaker moves off mike, it impossible to maintain the threshold for all conditions. The secondary effect is that the room ambience captured by open mikes also cut in and out leading to a very unnatural sound.

A much better solution is a concept that was invented in the 1970s by Dan Dugan of Dan Dugan Sound Design in San Francisco.

After several years of experimenting, Dugan came out with a patented system which was demonstrated to the Audio Engineering Society in 1974. Dugan’s method of automixing, which sets a maximum gain for the room and then smoothly mixes all microphones by splitting the overall room gain among all open microphones based on the signal levels at the microphone inputs, was patented by Dugan in 1975.

When one person speaks, that microphone’s gain level fades up instantly, while the other microphone gains are reduced. When the speaker pauses, all microphone input levels will adjust to medium gain to collectively match the level of one microphone at full gain. The resulting effect will be as if all speakers are sharing one microphone.

When several people talk at once, the remaining gain is shared. This dramatically reduces noise, feedback and comb filtering from adjacent microphones. Each individual input channel is attenuated by an amount, in dB, equal to the difference, in dB, between that channel’s level and the sum of all channel levels. It is not gates, compressing, limiting or automatic gain control, but available gain sharing across the open microphones. It works really well!

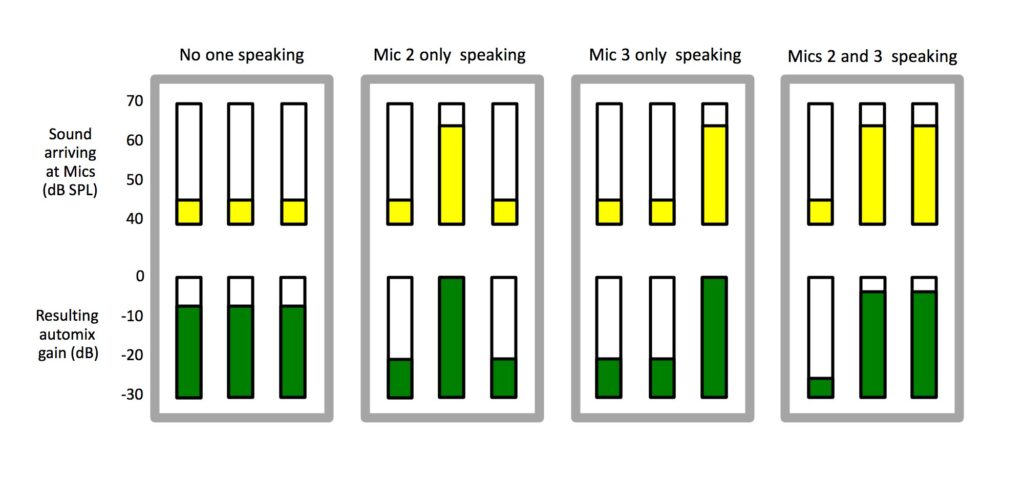

The figure below shows automixing with a three microphone system:

The first frame shows no one speaking. The sound levels at all microphone inputs are low. The system fades all channels to medium gains, adding them all up to match the level of one microphone at full gain.

The second frame shows one person speaking. The system automatically fades his/her gain to full level, while the other two inputs are turned down.

The third frame shows a different person speaking. The system automatically fades his/her gain to full level, while the other two inputs are turned down.

The fourth frame shows two people speaking simultaneously.

The system automatically shares the gain between them, while the other input is turned down. The automixer ensures that system gain remains consistent, even when several speakers are talking at the same time. They make perfectly matched crossfades, without any signal compression and without a noise gate that would cause undesirable artefacts.

Other manufacturers recognised the benefits of Dugan’s automatic mixing system, but due to his patent, had no choice but to develop alternate automixing techniques. One system developed by Shure was known as “adaptive threshold gating,” where a microphone is activated based on the ratio of the audio level at the mic vs. ambient room level. These worked, but suffered from the inability to adopt the gain sharing model.

Dugan’s own system languished for many years too. In the early 70’s he decided not to manufacture himself but rather licenced his technology to Altec. Altec implemented the technology in only a couple of their installation products and according to Dugan, did a poor job. The net result was that a great technology was not being used by the licensee, and no one else could use it either. This meant that for nearly 20 years everyone was presented with sub-standard automixing and of course, no one was really happy with using it. No wonder it had a poor reputation.

In 1993, Dugan’s patent expired. This freed him up to start manufacturing himself and other manufacturers could now experiment with the gain sharing concept. However, with the advent of digital boards, it meant his style of technology could be implemented as plugins. Yamaha’s CL, QL and TF series desks come with it built-in. Soundcraft, SSL and Allen & Heath have their versions and Waves produce a genuine Dugan plugin which means Avid, Digico, and other brands can all take advantage.

But is it worth it and does it work? Absolutely!

Since Yamaha added it to their QL series boards, I’ve been using it on nearly all of my gigs. I consistently get greater gain before feedback (as much as 16 dB), lower noise floor, consistent ambience and a much tighter sound due to less open mics at any one time.

I honestly cannot see myself doing conferences, panel discussions, unscripted events, and theatre without it.

A few hints:

Automixing should always be inserted post fade. That way, an off stage performer’s mic whose fader is down won’t affect the automix of the mics onstage whose faders are open. If you are running a lectern with two microphones, you don’t want those mics automixing between themselves as they’ll end up fighting each other for the available gain, even though they are covering the same source. The solution for this is to route the pair of microphones to a submix, insert a single channel of automix over the pair and then route the output to the main feed along with the other microphones.

Automixing has suffered a poor reputation for many years. But as the Dugan patent expired, he and others have been able to implement really good solutions that really work. Give it a go!

This article first appeared in the print edition of CX Magazine June 2018, p.28. CX Magazine is Australia and New Zealand’s only publication dedicated to entertainment technology news and issues. Read all editions for free or search our archive www.cxnetwork.com.au

Subscribe

Published monthly since 1991, our famous AV industry magazine is free for download or pay for print. Subscribers also receive CX News, our free weekly email with the latest industry news and jobs.